Flood plans and gardens: The City of London is preparing for climate change

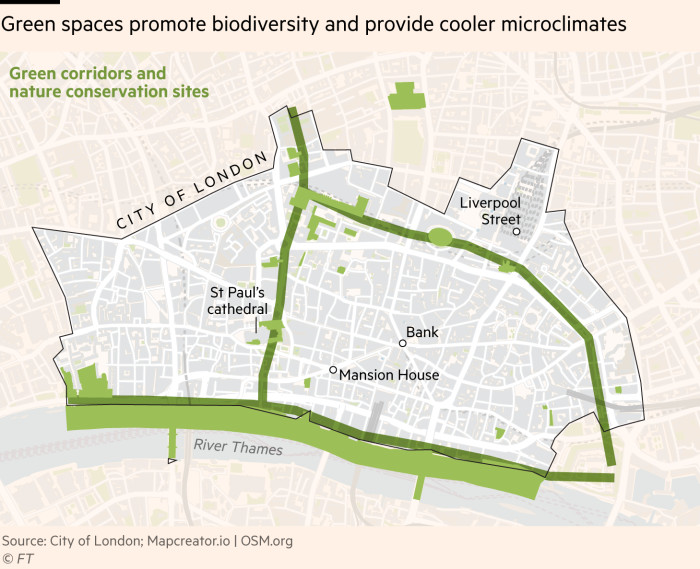

At Bank Junction in the heart of the City of London, freshly planted flowers spread over a very concrete surface. But these are not ordinary flowerbeds: they are part of the effort to prepare the historical financial district for the effects of climate change.

Beyond the Square Mile, the City of London Corporation is introducing environmental measures, from improvements to riverside walls for protection against rising tides to swapping British flowers for Mediterranean species suitable for heat.

The organization plans to invest £68mn between 2020 and 2027 in climate action. But this is only a fraction of the total money that will need to be spent in the coming decades to prepare the capital for a future of extreme weather.

The Thames Estuary 2100 project, the UK’s largest flood risk program designed to protect London’s estuary, is expected to cost £16.2bn when completed by 2100.

But climate experts worry that the City’s efforts to tackle global warming will not be enough if London’s poorer boroughs struggle to take the necessary action, as they raise questions about non-standard glass. work well with steel towers designed for a warmer world.

Bob Ward, chairman of the London Climate Ready Partnership, an association of government, business and community leaders focused on building extreme weather climates, said Square Mile was “a pioneer in London ” when it comes to preparing for climate change.

But, he added: “If the City of London does a good job, but other places don’t, someone else will suffer more. It is good that the City is doing what it can, but . . . it needs motivation [other boroughs] being equally active in solving the problem.”

Bank Junction embankments are made of granular fill material to retain surface water and prevent flooding. Rain from the road drains under one bed, while the other collects water on the pavement. Surface water flooding is expected to increase as climate change increases rainfall, and the City’s paved areas leave the area particularly vulnerable.

Alison Gowman is one of a group of senior men who serve as elected officials for the City’s local authority. As one of the most important financial districts in the world, ensuring that the Square Mile is prepared for the effects of climate change is important, he said.

“We are trying to balance the history of the City with the need to protect the City,” he added.

Many cities around the world have begun to face the challenge of adapting to climate change. Around $63bn worldwide was spent on adaptation in 2021-2022, according to a report from the Climate Policy Initiative and the Global Center on Adaptation, experts say this will need to increase rapidly in the coming years as the temperature is rising.

New York, which does not have the flood protection of London, is starting to buildnewnewfrontal.

Singapore is focusing on green areas, while Tokyo is focusing on developing a “solid preparedness system”, with normal disaster scenarios, “so that people know what to do.” what to do when clouds burst or rivers flow”, said Mark Watts, managing director of C40. , a group focused on making urban centers sustainable.

Climate change has hit the British capital, with severe flooding in 2021 and temperatures of 40C in 2022.

Emma Howard Boyd, former chair of the Environment Agency, the public body responsible for environmental protection in the UK, agreed that the City was well ahead of its peers in the capital when it came to its policy. of the river.

He added: “You’re only as good as your weakest link – that’s where you need co-operation across the whole of London.

The London Climate Resilience Review, commissioned by London Mayor Sadiq Khan, this month warned that the British capital was unprepared for the “disastrous effects” of climate change, with extreme flooding and extreme heat. who causes “fatal harm”.

It argued that although “significant climate change and resilience action” was taking place across London, it would not be enough to meet global warming.

The report called for an assessment of the economics of climate change adaptation and resilience, citing the National Audit Office, which said the government had “failed to quantify how much it spends on managing risks of drought, high temperatures and heat waves; floods and storms.

“Measures are taken by various government departments and agencies, and no one is collecting this information,” it said.

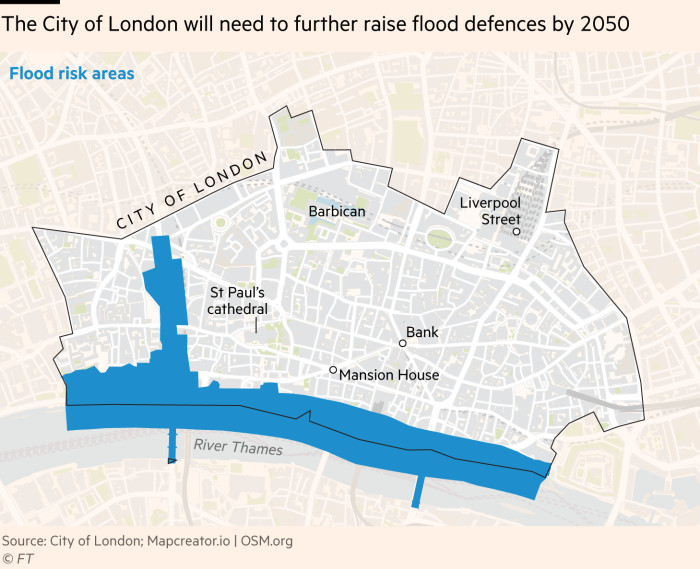

One of the biggest attractions of the Square Mile – its location near the river – is also an important attraction. The Thames Barrier, to the east of the City, and the embankments along the Square Mile’s 2km of riverfront have helped to protect the area from flooding.

The Environment Agency should make a decision about the future of the barrier in 2040, while the protection of the walls should protect the district for the next 25 years, said Tim Munday, the leading environmental development officer at the agency.

But Munday, who was out with his tape measure to check the walls, said these would need to be improved in the coming years and would be 50cm high in places 2050 and 100cm high in 2100.

Developers of new buildings along the river are being told to build these defenses now or ensure they can be easily built in the coming years, while owners of existing buildings along the Thames are being consulted about renovation of walls.

In some cases, the City will also be raised in relation to flood defences, and the ground level increased to ensure that new high walls do not obstruct views of the River Thames.

Doing this work will be especially difficult in places like Queenhithe, the only surviving Anglo-Saxon port in the world and an endangered monument. This is where balancing the City’s history and the impact of climate change will come together, Gowman said.

Elsewhere, the Whittington Garden, named after the former Lord of London Dick Whittington, was transformed from a “more formal garden” to one designed “on a low-water basis”, Gowman said. There is thyme and lamb’s ear, as well as other Mediterranean plants.

Paul’s Walk on the banks of the river, the organization has chosen to “plant a lot in the Mediterranean”, he added, while visiting the City. He said: “The English garden is not beautiful, but it works.

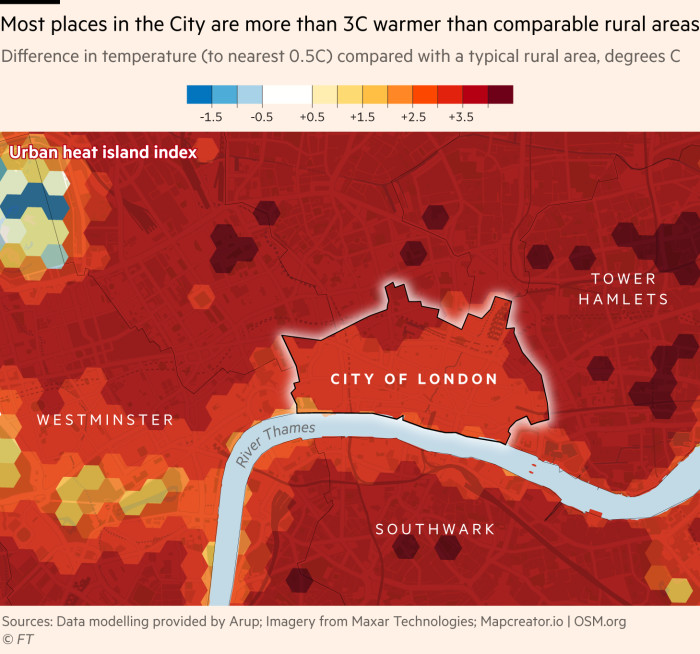

“Green corridors” are also being installed where plants and trees are used to create cool walkways. This planting is part of an effort to deal with the urban heat island effect, where the built-up area is much warmer than its surroundings. In some cases planting has reduced air temperatures between 3-8C during heat waves, the organization said.

The local authority has also installed 20 sensors across the City to measure temperature, pressure and humidity to understand the “micro-weather” across the Square Mile.

One morning in June, the sensor at Walbrook Wharf was almost 1C cooler than Holborn Circus. It also comes with sensors to measure soil moisture and runoff.

However, there are still concerns that the City’s buildings – especially the new glass and steel buildings – make the heat worse, especially when you use air conditioning to cool the buildings, then pump the warm air outside.

“We need to make sure that anything new we build is well suited to extreme temperatures,” said Ward, who has shutters, small windows and a roof painted white to reflect the weather. day.

Ward added that there needs to be a change in attitude towards building as the City warms up and accept that London is becoming a warmer place. He added that this would be important to avoid the “horrendous mistakes” seen in developments such as the Walkie Talkie building.

Ten years ago, the skyscraper had to be fitted with solar shading after the chicken design reflected sunlight onto the street below, causing heat damage to cars.

In a recent planning document, the agency said the city could expect 56 days of heatwaves – defined as three or more consecutive days with a temperature of at least 28C – per year by 2080 compared to days 14 in 2020.

It added that the City’s dense and urbanized environment is vulnerable to extreme heat, saying any new development should contribute “actively” to reducing the heat island effect.

Ward said all the climate change measures the City is taking are important, even if they come at an upfront cost.

He said: “The climate is changing and will continue to get worse until the world achieves zero greenhouse gas emissions.

But the economic issue [for adaptation] it could not be more clear,” he said. “These are investments to make sure that the City is able to deal with the situation in the future.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Check out the FT news here.

Curious about FT’s commitment to the environment? Find out more about our science-based goals here

#Flood #plans #gardens #City #London #preparing #climate #change