The call to end the nuclear power ban is bringing strong emotions to Australia

Liddell Power Station in Hunter Valley, Australia, burned coal for five decades before it closed last year. Opposition leader Peter Dutton now wants Liddell to be reborn as something that has been banned in the country for a quarter of a century: a nuclear power plant.

The New South Wales site is one of seven operating or closed coal-fired plants that Dutton, the leader of the centre-right Liberal party, has said could become nuclear power stations as part of the transition. growth in the way Australia produces its energy.

Nuclear power is what Australia needs for its “triple energy goals of affordable, clean and sustainable”, he said earlier this year.

Dutton’s position has pushed the energy policy ahead of next year’s election, as Australia – resource-rich and a major exporter of energy in the form of coal, liquefied natural gas and uranium – grapples with austerity. of it.

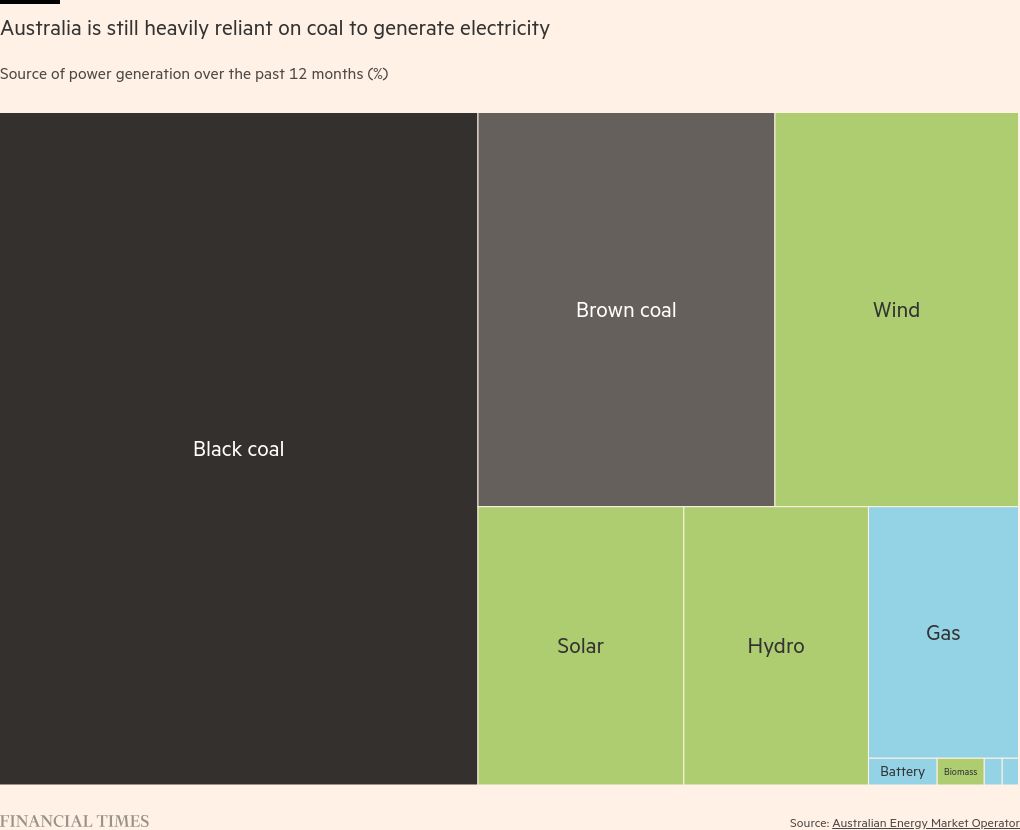

Anthony Albanese’s Labor Government has focused on renewable energy, passing legislation aimed at reducing carbon emissions by 43% from 2005 levels by 2030 and zero emissions by 2050. – a third of electricity generation last year – and to provide 82 percent of electricity from renewable sources by 2030.

But the opposition Liberals and their allies, the rural-focused Nationals, have vowed to abandon the 2030 target and scrap large-scale wind farm projects. They say nuclear power could provide power from the middle of the next decade.

Rising consumer power prices have dampened public enthusiasm for Labour’s renewables plans and opened the door for Dutton to offer nuclear as an alternative, said Ben Oquist, a former Greens political adviser. and a consultant at DPG Advisory Solutions.

“There is a danger that ‘unpleasant’ can trump ‘sophistication and fairness’ at the expense of life,” Oquist said.

Dutton’s plan would overturn decades of Australian policy and require changes to Australia’s state and federal laws restricting nuclear power.

This ban started in 1998, when John Howard’s conservative government gave it as a way to help small parties to support the construction of a research center near Sydney. It is still the only center in the country, which produces equipment for medical and industrial use.

But bipartisan opposition to nuclear power remains weak. A Lowy Institute poll this year showed 61 percent of those surveyed support nuclear as part of the nation’s energy mix, a sharp change from a decade ago, when the same poll showed 62 against it.

Another factor is the Aukus defense agreement with the US and the UK, which includes nuclear-powered submarines being built in Australia and will require the country to store radioactive waste. he is dangerous. In such circumstances, some argue that there is little reason to ban nuclear power.

Dick Smith, an aerospace and electronics entrepreneur, told the Financial Times that it would be a “disaster” for the country if it did not tackle climate change by using nuclear power.

“If Bangladesh and Pakistan can [it]so why can’t we?” Smith added, criticizing Labor politicians and conservation groups for being “opposed” to nuclear, a position he says many young citizens do not share.

It’s like religion. To think that you can run a modern industrial economy on solar and wind power alone is incredible. ”

Chris Bowen, Australia’s energy minister, called the opposition proposal a “nuclear scam” that was too expensive, too slow to implement and too dangerous.

A report in May by CSIRO, the government’s science agency, argued that developing nuclear power – whether by building large scale plants or small modular reactors – would they are more expensive than renewable ones and the construction of the plant will take at least 15 years.

“Long development times mean that nuclear will not be able to contribute to achieving total emissions by 2050,” the report concluded.

The nuclear controversy has also highlighted the looming gap in Australia’s renewable energy investment. The Clean Energy Council, a trade group for the renewables industry, said new commitments for renewable projects fell to A$1.5bn (US$1bn) by 2023 from A$6.5bn last year, while investors are struggling with planning permission for a slower, stronger environmental impact. valuations and higher labor and material costs.

The CEC said that only 2.8 gigawatts of renewable electricity was added to the grid last year, compared to the annual growth of 6GW needed to meet the government’s 2030 target.

Marilyne Crestias, interim chief executive of the Clean Energy Investors Group, which represents investors in renewables, said investment conditions have improved, but more is needed to improve confidence and be clear about the strategy.

“We need more climate and energy ambition, not less,” he said.

Jeff Forrest, a partner in LEK Consulting’s energy practice, said that nuclear power is “the 2040s solution to the energy problem we have today” and said there is confusion among investors and in the announcements that the plans are for the time being. long financial can be interrupted. the “left field” nuclear debate.

“Strong investments need stable and clear signals. That is very important for old investments, and no one wants to be pulled out from under them,” he said.

Near the Loy Yang coal-fired power station in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, local residents say the nuclear power plant will disrupt the owners’ plans to redevelop the site after the closure. center in the next decade.

Wendy Farmer, Gippsland organizer for Friends of the Earth and president of community group Voices of the Valley, said the proposal would threaten A$50bn of planned renewable investment.

“Are they telling investors to leave?” said the Farmer. “Putting nuclear weapons in these communities without consultation or negotiation with the owners of the land is an insult and a tyrannical strategy.”

Tim Buckley, director of the Climate Energy Finance think tank, said the opposition proposals would remove private funding through a “communist-style plan” that would require more than A$100bn of public funding.

“It’s not impossible, but it doesn’t make financial sense,” said Buckley, who questioned the political motive before the election. “This is not nuclear versus renewables. This is about expanding the climate wars.”

#call #nuclear #power #ban #bringing #strong #emotions #Australia